Beyond the Plate: The Ultimate Buying Guide for Durable and Stylish Everyday Dinnerware

Wednesday, February 18, 2026

Tuesday, February 10, 2026

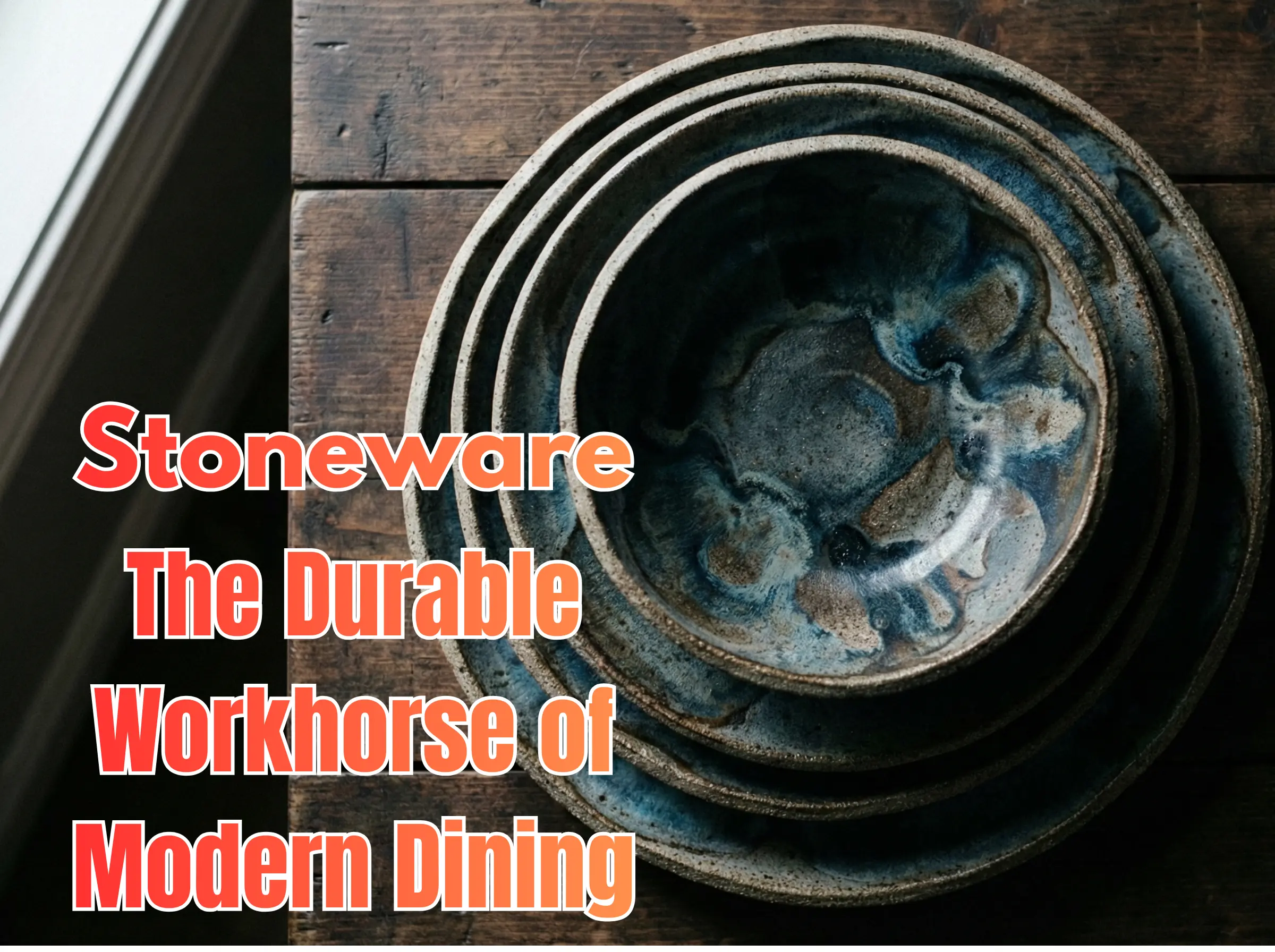

The complete encyclopedia entry on Stoneware. Understand the science of vitrification, the art of reactive glazes, and why this high-fired ceramic is the perfect balance between rustic earthenware and delicate porcelain.

Stoneware is widely considered the "middle ground" of the ceramic world, but this label does a disservice to its incredible versatility and beauty. It is the bridge between the rustic, porous nature of earthenware and the refined, glass-like quality of porcelain.

Named for its dense, stone-like quality after firing, stoneware is the material of choice for the majority of modern artisanal tableware, high-end restaurant service, and durable kitchen bakeware (like Le Creuset or Staub ceramics). It is prized not for its translucency, but for its rugged durability, its incredible capacity for complex glazes, and its tactile, earthy aesthetic.

This wiki entry explores the geological properties of stoneware, its pivotal role in the "Studio Pottery" movement, and why it is arguably the most practical material for daily use.

Stoneware is defined by its firing temperature and its physical state after firing.

While earthenware is fired at low temperatures (below 1150°C), stoneware is fired at high temperatures, typically between 1200°C (2190°F) and 1300°C (2370°F).

The magic of stoneware lies in vitrification. At these high temperatures, the silica (glass-forming agent) within the clay body melts and fills the microscopic pores between the clay particles.

One of the main reasons collectors and chefs love stoneware is Reactive Glazing.

Because stoneware is fired at such high heat, the glazes used on it can undergo complex chemical reactions that are impossible at lower temperatures.

Fig 1. High-temperature firing is crucial. The intense heat transforms the clay into a stone-hard, non-porous material.

Stoneware was developed in China as early as the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BC) and perfected during the Han Dynasty. The famous "Yixing" teapots (Purple Clay) are a specialized form of unglazed stoneware. The Chinese mastered high-temperature kilns thousands of years before Europe.

In Medieval Europe, Germany became the center of stoneware production (specifically in the Rhineland). They discovered Salt Glazing: throwing common salt into the kiln at peak temperature. The salt vaporized, reacting with the silica in the clay to form a bumpy, orange-peel texture that was incredibly durable. This created the famous German beer steins.

The modern appreciation for stoneware is largely thanks to Bernard Leach (British) and Shoji Hamada (Japanese). In the 1920s, they popularized the "Studio Pottery" movement. They rejected industrial mass-production in favor of the "honest," handmade aesthetic of stoneware. They championed the beauty of heavy, thick-walled pots, natural ash glazes, and visible throwing marks. This philosophy still dominates the handmade ceramic market today.

How does stoneware compare to its siblings?

| Feature | Earthenware | Stoneware (This Article) | Porcelain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Firing Temp | Low (1000°C) | High (1200°C - 1300°C) | Very High (1300°C+) |

| Porosity | High (absorbs water) | Non-Porous (Vitrified) | Non-Porous (Vitrified) |

| Durability | Low (Chips easily) | High (Very tough) | High (Hard but brittle) |

| Light Transmission | Opaque | Opaque | Translucent |

| Color | Red/Terracotta | Grey, Buff, Brown, Speckled | Pure White |

| Typical Use | Flower pots, decorative | Dinnerware, Bakeware | Fine dining, tea sets |

The "Tap" Test:

Stoneware is arguably the most practical material for a busy, modern kitchen.

Fig 2. Stoneware's thermal retention makes it ideal for oven-to-table serving.

One of stoneware's biggest advantages over porcelain is its thermal shock resistance. While you should never take a ceramic straight from the freezer to a hot oven, stoneware heats up evenly and holds heat incredibly well.

While tougher than earthenware, stoneware is heavy.

Choosing stoneware is a choice for substance and texture. It lacks the pretension of bone china and the fragility of earthenware.

Whether it is a mass-produced set from a major retailer or a hand-thrown bowl from a local artist, stoneware brings a grounding, elemental presence to the table. It reminds us that we are eating from the earth, transformed by fire into stone. For the daily ritual of eating, there is perhaps no better companion.