Beyond the Plate: The Ultimate Buying Guide for Durable and Stylish Everyday Dinnerware

Wednesday, February 18, 2026

Monday, February 16, 2026

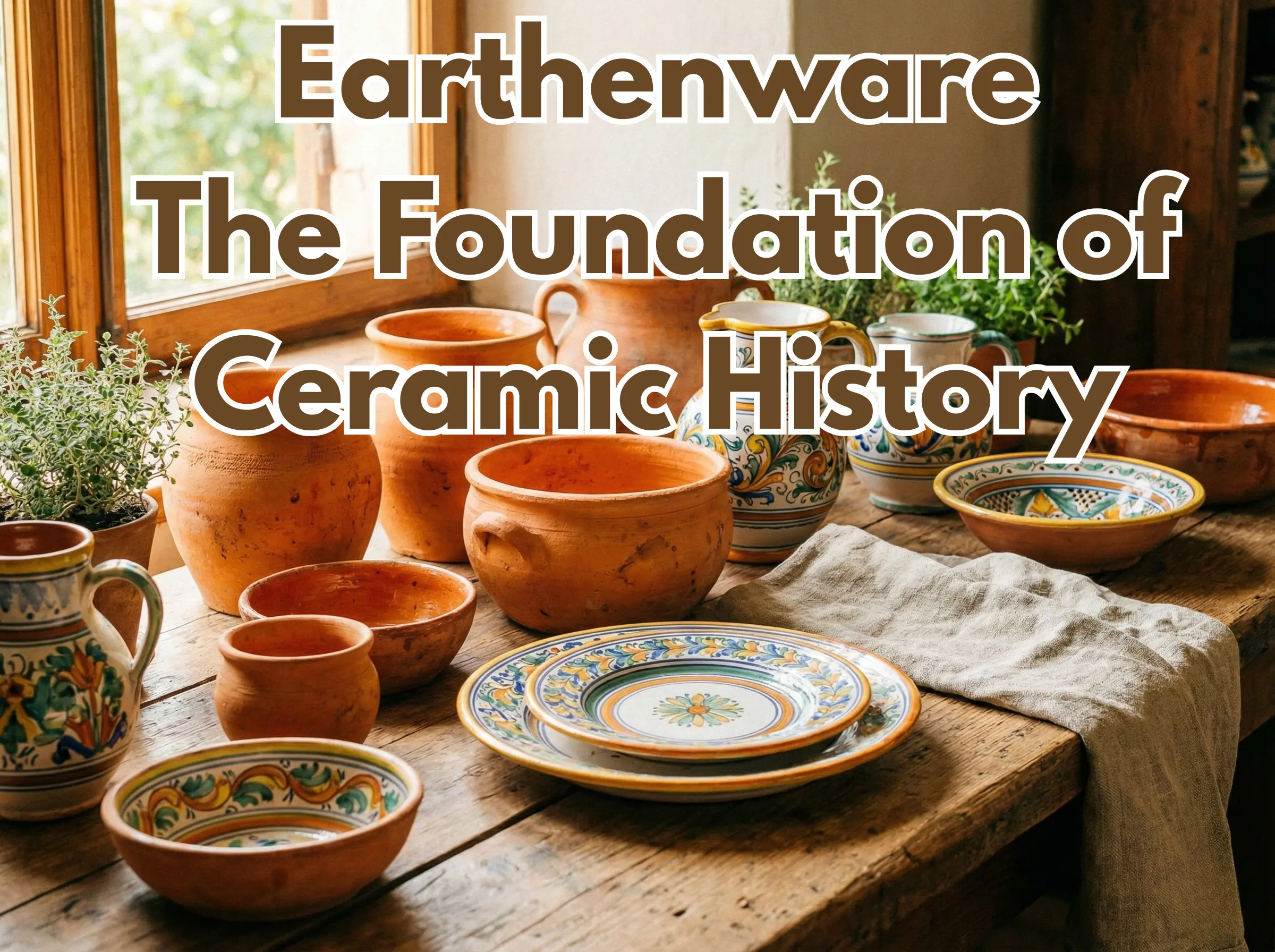

An in-depth encyclopedia entry on earthenware clay. Explore its ancient origins, distinct material characteristics, comparison with stoneware and porcelain, and its enduring role in modern tableware.

Earthenware (陶器) is one of the oldest and most universal materials used by humankind. It is the foundation upon which the entire history of ceramics is built. As the most porous and lowest-fired form of pottery, earthenware possesses a unique warmth, a varied history, and specific material properties that distinguish it from its denser counterparts, stoneware and porcelain.

This wiki entry delves into the science, history, and practical applications of earthenware, providing a comprehensive understanding of this essential material.

At its simplest definition, earthenware is clay fired at relatively low temperatures—typically between 1,000°C (1,830°F) and 1,150°C (2,100°F).

Unlike stoneware or porcelain, earthenware does not reach the point of complete vitrification (the process where clay particles melt and fuse into a glass-like, non-porous substance). Because the clay particles do not fuse completely, the finished body remains microscopically porous.

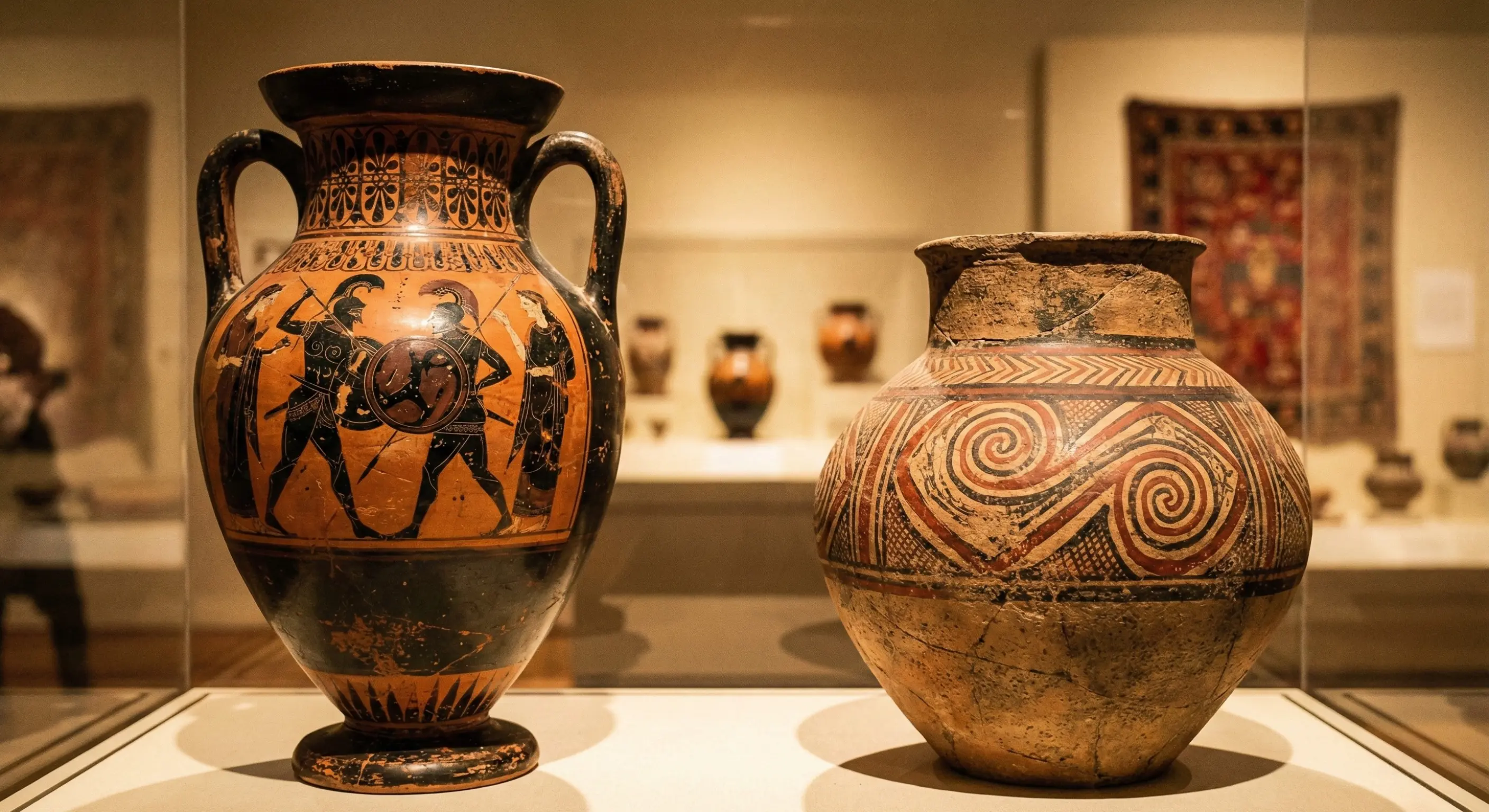

Earthenware is not just a type of ceramic; it is the first ceramic. Its history is synonymous with the dawn of human civilization.

Before humans learned to build high-temperature kilns capable of producing stoneware, they used open bonfires or simple pit kilns. These primitive firing methods could only achieve the lower temperatures required for earthenware.

Fig 1. Ancient earthenware forms showing diverse cultural expressions, from refined Greek painting to Neolithic geometric designs.

Understanding earthenware requires contextualizing it within the broader ceramic spectrum. The primary differences lie in the clay composition, firing temperature, and resulting density.

| Feature | Earthenware (陶器) | Stoneware (炻器/石器) | Porcelain (瓷器) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Firing Temp | Low (1000°C - 1150°C) | Mid to High (1200°C - 1300°C) | Very High (1300°C - 1400°C+) |

| Porosity | High (>5% absorption). Porous unless glazed. | Low (<1-2% absorption). Vitrified or semi-vitrified. | None (<0.5% absorption). Completely vitrified. |

| Body Color | Terracotta red, brown, cream, buff. | Often grey, tan, or brown tones. | Pure white. |

| Translucency | Opaque. | Opaque. | Translucent when thin. |

| Durability | Less durable, prone to chipping. | Very durable, hard, chip-resistant. | Extremely hard and durable, but brittle. |

| Sound (Tap Test) | Dull "thud" sound. | Clear, ringing tone. | High-pitched, bell-like ring. |

Note: This table provides general guidelines. Modern hybrid clays and firing techniques can sometimes blur these boundaries.

Earthenware appears in many forms, depending on the clay used and the glazing technique applied.

Italian for "baked earth." This is the most recognizable form of earthenware. It refers to unglazed, fired clay, usually reddish-brown due to high iron content. It is widely used for flower pots, architectural roofing tiles, bricks, and sculptures. Because it is unglazed and porous, it is rarely used for dining surfaces today.

As mentioned in the history section, this category includes Majolica, Faience, and Delftware. It is characterized by a reddish or buff clay body covered by a thick, opaque white glaze, which serves as a base for colorful painted decorations. The glaze gives it a smooth, hygienic surface suitable for tableware.

Developed in 18th-century England, most notably by Josiah Wedgwood. Potters refined earthenware clays, removing impurities to create a lighter, cream-colored body. When covered with a clear lead glaze, it resembled porcelain more closely than coarser earthenware. It became an affordable, refined alternative to expensive imported Chinese porcelain and laid the foundation for the modern British ceramic industry.

Today, earthenware remains a popular choice for tableware, though it occupies a different niche than stoneware or bone china.

Fig 2. Modern earthenware is prized for its rustic aesthetic, thick walls, and warm appeal in contemporary kitchens.

Earthenware is the humble ancestor of all ceramics. While it may lack the sheer strength of stoneware or the ethereal translucency of porcelain, its historical depth, aesthetic warmth, and vibrant decorative potential ensure it remains a beloved and essential material in the world of tableware. Understanding earthenware is understanding the very roots of human craftsmanship.